For years, the Democratic Alliance (DA) has marketed the Western Cape as proof of its superior management, the “model province” that allegedly demonstrates what good governance can look like in South Africa.

The recent scandal involving Western Cape Premier Alan Winde has cracked open that illusion. Though he has denied wrongdoing, reports that Winde may have accepted illicit payments from contractors linked to provincial tenders have triggered public outrage and raised difficult questions about the DA’s moral high ground.

For a party that has built its national reputation on the rhetoric of “clean governance”, the allegations land heavily.

They are not merely about one man’s conduct, but about the culture that has taken root under decades of uninterrupted DA rule in the province.

It is easy to see why the DA’s narrative has been so persuasive. The Western Cape appears, at first glance, to run smoothly: roads are clean, power outages are shorter, and municipal accounts are processed with bureaucratic precision.

But for millions of residents who live outside the postcard images of Sea Point and Constantia, the experience of governance tells another story.

Residents in areas such as Delft, Wallacedene, Khayelitsha and Blikkiesdorp have long complained that their monthly water and electricity bills are higher than what many suburban households pay, despite the latter consuming far more.

Social housing tenants in the inner city speak of being trapped in a system where the City of Cape Town charges premium rates for unreliable services.

Sewage leaks often go unrepaired for weeks; water cuts and power faults are routine.

In some housing developments, tenants are served with eviction notices for arrears they can barely understand, debts inflated by opaque billing systems that no one seems able or willing to explain. This is not mismanagement in the accidental sense.

It is the product of a deliberate model that prioritises fiscal discipline over social equity.

The DA’s obsession with “balancing the books” has created a city that is efficient for some, but extractive for most.

The poor pay more for less, while the wealthy enjoy uninterrupted service and the comfort of insulation from the daily collapse of the state elsewhere.

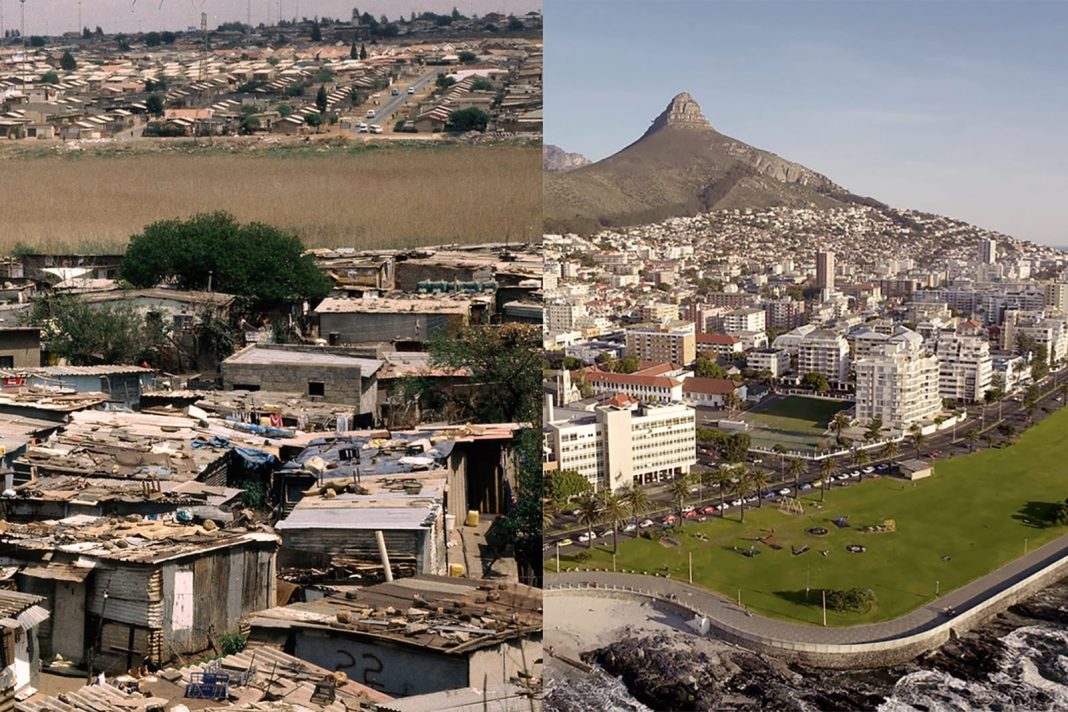

Nowhere is this disparity more visible than in the physical layout of Cape Town itself.

Three decades after apartheid’s official end, the city remains one of the most segregated in the world. Informal settlements such as Blikkiesdorp, Marikana, and Wallacedene stand as living monuments to the failure of “effective management”.

Originally designed as temporary relocation areas, these spaces have become permanent zones of abandonment, corrugated metal ghettos on the edge of an otherwise gleaming metropolis.

Residents complain of raw sewage running through pathways, intermittent electricity, and overflowing refuse points.

Many have waited decades for housing opportunities that never arrive, while land in the inner city is auctioned to private developers in the name of “urban renewal”.

The City’s defenders often counter that the DA cannot be blamed for apartheid’s spatial design.

But after nearly two decades in power, the argument rings hollow.

The persistence of this geography is no longer a legacy, it is policy.

By prioritising property rates, zoning laws, and investor confidence, the City has ensured that land continues to accumulate in the hands of the few, while the majority remain locked out of the urban core.

Even the so-called well-managed parts of the city are beginning to buckle.

In recent years, Cape Town’s infrastructure, once the DA’s proudest boast, has shown signs of neglect and decay.

Sewage spills have contaminated beaches along the False Bay coastline, forcing temporary closures at Fish Hoek and Muizenberg.

Ageing water networks leak thousands of litres daily, and the city’s electricity grid, though better maintained than Eskom’s, suffers from chronic faults in poorer districts.

Stormwater drains overflow with each heavy rain, flooding informal settlements that were never meant to exist but now house tens of thousands of people.

Behind the statistics lies a moral problem: the DA governs as if the poor are an inconvenience rather than citizens.

Yet Cape Town today is a city haunted by violence, a metro where the sound of gunfire is as common as the hum of traffic.

Entire neighbourhoods, from Hanover Park to Mitchells Plain and Manenberg, live under the shadow of rival crews that fight over drug turf, extortion rackets, and recruitment of young boys.

The murder rate in the Cape Flats routinely exceeds that of most war zones.

Gangs collect “taxes,” control informal transport routes, and mediate disputes in the absence of functioning policing.

In effect, Cape Town has become a dual city: one where law and order exist for the rich, and an alternate regime of fear governs the poor.

For decades, rival associations have waged bloody wars over routes, often paralysing large sections of the city’s transport system.

The provincial government’s response has been reactive.

When people are killed in Cape Town, few expect justice. Confidence in the police is abysmally low, particularly in townships where corruption, incompetence, and under-resourcing are endemic.

Victims of violence often describe reporting crimes only to be met with indifference or outright hostility.

Case dockets disappear; investigations stall for years; witnesses are intimidated into silence.

Local enforcement structures, including metro police, and private security networks, are deeply intertwined with provincial policy.

In wealthier suburbs, these systems work in seamless coordination, offering rapid response and deterrence.

In the townships, they are almost invisible.

Residents report that when City officials do intervene, it is often through punitive by-laws, forced evictions, or the demolition of informal structures rather than meaningful protection or service.

Reports of tender manipulation, preferential treatment of developers, and internal patronage networks have become too frequent to dismiss.

The Winde bribery scandal is only the latest in a series of controversies that suggest the Western Cape’s administrative machinery is neither as transparent nor as incorruptible as it pretends to be.

Cape Town’s contradictions expose the hollowness of the DA’s mythology.

The city that markets itself as Africa’s best-run municipality is also one of the continent’s most unequal; its “world-class” reputation rests uneasily atop an underclass of dispossession and despair.

The Leader of the Opposition in the Western Cape Provincial Legislature Khalid Sayed the Western Cape Premier and the DA paint an image of a thriving and well-governed province.

He said for example housing remains one of the Western Cape’s greatest crises, yet under the DA-led government, it has been marked by mismanagement and evictions that disproportionately affect the most vulnerable.

“Take Communicare, for example. Despite national intervention and a forensic investigation into the acquisition of its properties, evictions have continued, forcing pensioners from their homes. This is just one example of the province’s disregard for the poorest citizens,” he said.

Municipal failures are equally glaring. In Swellendam, Saldanha Bay, Matzikama, and Garden Route District, governance is in disarray, with financial mismanagement and corruption allegations mounting. Swellendam’s council failed to release the Vermaak Report on municipal misconduct, while Saldanha Bay lost R2.5 million in public funds amid a housing backlog.

He said these examples expose the DA’s failing model of governance – one that claims efficiency but delivers scandal after scandal.

The Premier ended his speech with the words, “The Western Cape Government is for You.” But who is the “you” he refers to? Wealthy business interests or the working-class residents of this province? As we mark the 70th anniversary of the Freedom Charter, we must ask ourselves: which side is the DA on? The side of ordinary South Africans striving for a better life, or the side of economic recklessness and entrenched inequality?